When it comes to sports in America, injuries are often front and center in the public eye. From the NFL to high school fields, journalists play a crucial role in shaping how these incidents are understood by fans and the wider public.

Typically, injury coverage ranges from real-time updates during games to in-depth features on recovery and long-term health. However, the reporting of head injuries, and particularly chronic conditions like Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), requires a level of care and responsibility that goes beyond the usual play-by-play.

What is CTE?

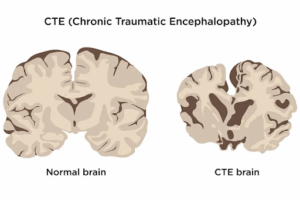

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease linked to repeated head trauma, such as concussions and subconcussive blows. Once thought to be rare, CTE has become a hot topic in American sports, particularly football, boxing, hockey, and soccer.

The disease is characterized by the buildup of abnormal tau proteins in the brain, leading to symptoms that can mimic or overlap with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and other neurological disorders

CTE can only be definitively diagnosed after death, through brain tissue analysis. However, research has shown that the risk is highest among athletes with a history of repetitive head impacts, especially those who played contact sports for many years

Who is at Risk?

While CTE is most commonly associated with professional athletes, recent studies show that even young amateur players are not out of the woods.

A 2023 NIH-funded study found that over 40% of brains donated by contact sport athletes under 30 showed signs of CTE, most in the early stages. The vast majority of these athletes played American football, but cases were also found in soccer, hockey, wrestling, and rugby. Strikingly, most had only played at the amateur level, underscoring that you don’t have to be a household name to be at risk.

Among former NFL players, the numbers are even more sobering. The Boston University CTE Center found evidence of CTE in 91.7% of the 376 former NFL players studied, though researchers caution that this figure may be inflated by selection bias, as families are more likely to donate brains of those who showed symptoms. Still, the correlation between repeated head trauma and CTE is as clear as day.

Symptoms and Progression

CTE symptoms typically develop years or even decades after the head injuries occurred. Early signs include confusion, headaches, and dizziness. As the disease progresses, individuals may experience memory loss, poor judgment, impulsivity, depression, and even suicidal thoughts.

In later stages, movement disorders, speech problems, and severe cognitive decline can develop, leaving individuals a shadow of their former selves.

It’s worth noting that not everyone with a history of head trauma develops CTE, and symptoms can be influenced by other factors such as genetics, mental health, and life circumstances.

The Role of Sports Journalism

Sports journalism sits at the crossroads of entertainment, public health, and ethics. How journalists report on injuries (especially head injuries) can shape public perception and even influence policy.

Historically, there has been a tendency to downplay concussions, using terms like “got his bell rung” or “just a little ding,” which can minimize the seriousness of these injuries. However, in recent years, there’s been a shift toward more accurate and responsible reporting, particularly as the long-term risks of CTE have come to light

Responsible sports journalists are now encouraged to use precise medical terminology, avoid speculation, and provide context about the potential long-term consequences of repeated head injuries. This shift not only helps educate the public but can also drive changes in safety protocols and league policies.

For those interested in making a difference in this evolving field, pursuing a sports journalism degree can provide the skills needed to cover these complex issues with accuracy and integrity. Programs across the US offer specialized training in sports reporting, multimedia storytelling, and ethical considerations, preparing the next generation of journalists to “call it like they see it,” while also keeping athlete health at the forefront.

There’s no silver bullet for preventing CTE, but awareness is half the battle. Improved helmet technology, rule changes, and better sideline protocols are steps in the right direction. Most importantly, a culture shift is needed; one that values long-term health over short-term glory.

As the saying goes, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” By promoting honest conversations about risk, supporting research, and holding leagues accountable, journalists, athletes, and fans can work together to protect the future of sports.

For those seeking more details on CTE, the National Institutes of Health, Mayo Clinic, and Cleveland Clinic all offer comprehensive resources on symptoms, diagnosis, and ongoing research.